But It’s Not Porn: The Aesthetics of Desire

Why should we re-examine socially accepted images of the naked female form in terms of an art historical context, rather than obscenity, when considering the objectification of women in modern society?

……….

But It’s Not Porn…

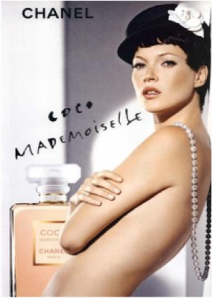

When comparing an erotic image of a naked female and a Coco Mademoiselle advert also depicting an unclothed woman, the context of the circulation of the images is often enough to judge which to label as ‘porn’ and which to publicly accept. What is it about the structuring of these images that leads to the censorship of one and endorsement of the other –in spite of the objectification of the female body still inherent in the ‘tasteful’ image. Has our focus upon which image is regarded as pornographic and which possesses a pleasing aesthetic overlooked the objectification still implicit in adverts?

I will argue that the problematic in the circulation of the advertisement can be related to an art historical lineage of images of the naked female form evading censorship. In a series of examples I will examine how the formal qualities of depictions of women have excused the moral content of the work under the veil of aesthetic consideration. Unlike porn, which is unquestionably a social taboo, the politics surrounding the objectification of the female form are eclipsed, in preference for a focus on theoretical debate.

Following the argument of Susan Sontag in her essay On Style, I will propose that this difference in responses to the erotic and porn is formed by the fact that pornography has content, which invokes response, whilst art induces contemplation. I will contend that we have still failed to recognise that the very structuring of this contemplative space for the viewer, as part of their aesthetic experience of art, is still a moral quality[1] that needs reaction and readdressing as much as the porn.

……….

Arousal vs Contemplation

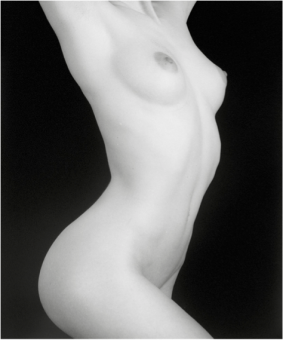

Pornography (Fig 2) has a natural tendency to attract censorship since it complies to the terms of reports such as the Williams’ committee report of 1979[2] which looked at Obscenity and film censorship: ‘ A pornographic representation is one that combines two features: it has a certain function or intention, to arouse its audience sexually, and also has a certain content, explicit representations of sexual material (organs, postures, activity, etc).’ [3]

In Figure 2 we do indeed see that there is a clear direction of the viewer’s gaze to the woman’s genitalia and the blankness of the subject’s gives no hint at any interior consciousness beneath the surface of the image. The content is a construct of the fantastical projections of the viewer’s imagination. All the signs leave us in no doubt that the image is pornographic, rather than a directive to an artistic higher appreciation, and should therefore be tightly censored.

……….

Misleading Metaphors

On the other hand the metaphorical style of an ‘artistic’ image invites interpretation and, by this reasoning, apparently needs no moral justification. The subject matter is annihilated by the intelligence of the imagination.

However, metaphors can mislead, due to their capacity to evoke multiple interpretations and, according to Sontag, the interpretation they elicit ‘makes art manageable’, overlooking questions of morality and acceptability[4] -we have been seduced by the style of an artistic work.

In place of a quest for the meaning of content, I suggest that we should therefore also question the politics of surface. In doing so we can actually see what the image is – as in the case of the pornographic image – rather than allowing the seduction of form to lead us directly to the ‘higher’ understanding that we assume art to represent.

I propose that it is this same stylistic ‘trick’ that is employed in the Chanel advert in order to legitimise the underlying message that ‘sex’ sells’. I will firstly therefore examine the advert’s artistic heritage and how these images of the female form comply to Sontag’s theory.

……….

Covering Up

Fig 3: Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, c. 1484-86, tempera on canvas http://perceptionoffemalebeauty.blogspot.co.uk/2011/05/birth-of-venus-sandro-botticelli-1483_08.html

Roger Scruton has argued that the fleshy softness of the painted figure in Boticelli’s Birth of Venus, c. 1484-86 (Fig 3) lures our imaginations beyond the body into the realms of metaphorical embodiment[5]. This apparently denies our desire as it arouses it – expressing decency rather than exposure. In his view, the painting thereby evades pornography’s tendency to deny the human subject and elicits what he terms a ‘disinterested interest’, as opposed to mere arousal.[6]

Scruton may argue that Venus’ withdrawn gaze hints to an inner self knowledge and individuality[7], however, the framing of this demure, mystical gaze which does little to interrupt the viewer’s appreciation suggests that: ‘women are meant to look perfect, presenting a seamless image to the world…the position of woman as fantasy thus depends on a particular economy of vision’.[8] The abstracted symmetry and colouring of her body has produced an iconic objectified figure, pinned to a flat background and, the distanced gaze, far from suggesting an inner autonomy, was linked by Freud to the ‘lack’ of the female genitalia. By this reasoning the sex that is covered by Venus’ hair is in fact emphasised and evokes desire.

The artistic construction of the painting, whereby the incongruity between the sexuality implied by the looseness of the hair is tempered by the overtly symbolic attempts to both uncover and clothe, has allowed for a moral sanctioning of the pleasurable consumption of the female form. Indeed, the very notion of uncovering via the symbolism of the covered is in itself an implicitly fetishist mode of representation that must be addressed.

……….

The Cult of Beauty

Venus’ ‘union of strangeness and puissant loveliness with depth and remoteness of gaze’[9] which, renders her a bearer rather than maker of meaning, alludes to the cult of beauty that formed around the work of Pre-Raphaelites such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti who rendered the subjects of his paintings ‘not as she is, but as she fills his dream.’[10]

Fig 4: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Bocca Bacciata (1859): http://www.rossettiarchive.org/zoom/s114.bmfa.img.html

The eroticism of Rossetti’s paintings were more contested at the time than the exposure of flesh in the case of Venus however, it was the same formal qualities of the painting that eventually secured their positioning within the artistic canon and allowed their subjects to be visually consumed in public.

Rossetti’s cropped figures of the 1950s (Fig 4) are trapped in sumptuous ornate spaces mimicking the sensuality of the exposed areas of skin – un-censoring the image through a conflation of setting and body. As in the case of Botticelli, however, I suggest that this actually creates a fetishist frame in which the beauty of painting is equated with the woman as beautiful. Body parts become fore grounded as symbols and the female form – as with Venus – becomes a representation. Woman is a symbolic object who cannot transcend the framing of an implicitly voyeuristic gaze.

……….

Modernity, Mulvey and Mappelthorpe

The conflict between aesthetic seduction on the one hand and derogatory fetishism on the other, has been explored more recently by Laura Mulvey in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Here, she suggests that issues of morality in art have been compounded by the invention of the camera, film and cinema. These have lent a feeling of actuality and immediacy to nevertheless ‘unreal’ images and therefore made it easier to sublimate fetishist imagery into the viewer’s consciousness. Essentially, in terms of feminist criticism, the ‘beautiful’ images of women in art became more potent in the naturalism of the camera’s lens.

This also leads me to the work of Robert Mappelthorpe and his framing of the human form. Like Rossetti before him, he employs formal techniques, which seduce us into an aesthetic rather than erotic contemplation of the work . In this way we again overlook arguments concerning the objectification of the body. For this reason, although he depicts men as well as women, he is relevant to the way in which modern advertising structures our gaze to find images acceptable and inviting (rather than offensive due to their objectification of the subject).

In my opinion, as with Rossetti, Mapplethorpe’s exploration of the erotic is evident in the surface of the photographs. In spite of this and, in light of controversy over the extent to which they arouse the viewer, they are considered as ‘art’ rather than ‘porn’. I suggest that this is mainly due to the way in which he manipulates the camera’s gaze as a stage in to explore the erotic within the boundaries of the aesthetic.

The focus is intent upon the human from, pushing the onlooker outside the frame and building the physical beauty of the image into something that is satisfying in itself – or what Mulvey alludes to as: ‘a hermetically sealed world which unwinds magically, indifferent to the presence of the audience’[11]. Suddenly, what may have been considered risqué is merged with the onlookers’ psyche, creating an interior to the photograph accordant with the classical ideals of the contemplation of beauty being for its own sake, in its presented form, rather than being considered pornographic.

Fig 5: Robert Mappelthorpe, Mayanne, gelatin silver print, 1988: http://www.mapplethorpe.org/exhibitions/2009-02-12_marc-selwyn-fine-art/

This tension is evident in Images such Maryanne, 1988 (Fig 5) where the formalistic quality has been utilised in defence of his work from the branding of ‘obscenity’. Janet Kardo, curator of the 1988 Mappelthorpe show ‘The Perfect Moment’ identified this when she asserted: “although his models often are depicted in uncommon sexual acts, the inhabitants of the photographs assume gestures governed by geometry, and they are shown against minimal backgrounds” [12] Indeed it is true that with their intense focus upon the artistry of the postures, often shifting the eye from flesh to fabric, the images are as much examples of still life as his images of flowers.

I suggest, however, that it is this – rather than the exposure of flesh – wherein lies the moral problem. The idiosyncratic curves and softness of the subjects of Mappelthorpe’s images, whether male or female, that save them from censorship, have a disconcerting resemblance to the ideals of the female form I have examined in earlier paintings. The gender or nature of the subject does not therefore matter, since the photographs still clearly postulate a vision of the female form as being the one of ideal beauty. Woman still symbolises ‘other’, simply with the objectification masked by the surface style and androgynous construction of work in series.

……….

Mappelthorpe and Mademoiselle

How does this problematic relate to the ‘Coco Mademoiselle’ image? Firstly, as with Mappelthorpe’s photography, the model shares in the material conditions of the photograph. Again, the heightened realism of the image that bears no demarcation that this is ‘an image of’, allows the viewer to live within a perfect flow with the image that robs the body of interiority in place of a utility to the merchandise.

Much like the Rossetti painting which, merges sensuality of material with that of skin, the heightened allure of the female body, accentuated by the curve of the pearls and complementary colouring of perfume and skin tone, invites a ‘gaze beyond’- through the model’s vacant stare and flat planes of the composition to the material product.

In the same way that the metaphorical nature of the Botticelli and Rossetti’s paintings rendered the body a fetishist object here, the female subject is eclipsed into a realm of fantasy, based on a sensual experience of the material lifestyle that she acts as an un-autonomous symbol for. It is therefore by the same aesthetic techniques of their ‘art’, that we circulate images of a clearly objectified female without thought, and yet censor porn due to its ‘obscene’ nature.

……….

Conclusion

An artistic image may not be subject to censorship – due to the masking of pornography under the guise of the aesthetic –however, it may still be sexually violent. Indeed, I have argued that the cloaking of violence beneath a seductive surface of ‘art’, which makes it less offensive to ‘reasonable people’[13], renders it more problematic.

These freely exhibited images directly feed into our wider cultural values by way of academic discussion and critique. They therefore subliminally ingrain a sexist ideology within society – with a certain perspective on the perfection of the female form – that is just as unrealistic as porn. Despite this they are less easy to censor than pornography due to their interpretative nature and are therefore arguably more dangerous. The recent rise in cosmetic surgery and adherence to beauty marketing campaigns, which mimic the formal qualities of the historical rendering of the female form in art, pays clear testimony to this.

We should not, therefore, lose sight of this objectification in deference to definitions of art as that which encourages ‘contemplation’ and ‘imaginative transposition’ [14] . I suggest rather that we continue to challenge the obscenity beneath aesthetic seduction since it is still a relevant and pressing concern.

……….

Bibliography

- Susan Sontag. Against Interpretation; Penguin Classics; 2009

- Scruton R. Beauty. Oxford University Press; 2009

- Pollock G. Vision and Difference. Routledge Classics; 2003

- Pollock G. Differencing the Canonroutledge; 1999

- Korsmeyer C. Aesthetic Pleasures. In: Gender and Aesthetics. Routledge; 2004

- Kidd D. Mappelthorpe and the new obscenity. From: after the image, Vol 30 2003. Questia. Accessed 13/3/2012. Available from: http://www.questia.com/googleScholar.qst?docId=5001701236).

- Mulvey L. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In: Screen 16.3 Autumn; 1975

- Manchester Colin. Obscenity, Pornography and Art. Available from: http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/cmcl/malr/421.pdf

- Dworkin Andrea. Pornography, Men Possessing Women. E.P Dutton; 1989

- Gilbert-Rolfe Jeremy. Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime. Allworth Press; 1999

- Dines. G. Pornland, How Porn has Hijacked our Sex

[1] Susan Sontag. On Style. In: Against Interpretation; Penguin Classics; 2009 ed; pp.22-24

[2] Manchester Colin. Obscenity, Pornography and Art. Available from: http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/cmcl/malr/421.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] Susan Sontag. Against Interpretation. In: Against Interpretation; Penguin Classics; 2009 ed; p8

[5] Scruton R. Beauty. Art and Eros. In: Beauty. Oxford University Press; 2009; pp.154-159

[6] Ibid.

[7] Scruton R. Beauty. Art and Eros. In: Beauty. Oxford University Press; 2009; p155

[8] Rose J. Quoted in: Pollock G. Woman as Sign. In: Vision and Difference. Routledge Classics; 2003; p 166

[9] F.W.H Myers Quoted in: Pollock G. Woman as Sign. In: Vision and Difference. Routledge Classics; 2003; p 172

[10] Rossetti C quoted in: Pollock G. Woman as Sign. In: Vision and Difference. Routledge Classics; 2003

[11] Mulvey L. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In: Screen 16.3 Autumn; 1975

[12] Kidd D. Mappelthorpe and the new obscenity. From: after the image, Vol 30 2003. Questia. Accessed 13/3/2012. Available from: http://www.questia.com/googleScholar.qst?docId=5001701236).

[13] Ibid; pp 33

[14] Lord Clarke Quoted in: Ellis John. On Pornography. In: Pornography: Film and Culture, ed. Lehman Peter. Rutgers; 2006; pp.29